Presented for Introduction to Lifestyle Medicine, Harvard Extension School: PSYC E-1037

Notes by Sang H. Kim, Ph.D.

These notes are intended as additional resources for my brief presentation on October 21, 2014, for Introduction to Lifestyle Medicine, which is a Psychology Extension course at Harvard University. This is based on my personal notes while preparing for the research and the published research findings.

Clinical Controlled Trial Using MBX-12 as Core Protocol

Background: What Body Knows

Our body remembers what we experience every day, especially the shocking memories of traumatic events, learns from them and adapts to what comes next. The memories are stored not only in the brain but in the body. As memories stored in the brain affect the body, the information collected in the body does the same to the brain. They reciprocally share stored information, often causing an abnormal reaction, triggered by memories, to a certain event, people, place, smell, or sound.

When the information shared counter-balances each other, with the brain keeping the body in capable condition and the body facilitating sufficient provisions of energy, the optimal condition of the self is maintained. When imbalanced, incremental discrepancies develop. When the gaps go unchecked for a prolonged period, the reciprocal chain weakens, and may in the end break, leading to health problems such as traumatic disorders. The less the brain and body communicate, the less we are capable of coping with the stress.

To bring back the relationship between body and brain, we need to do something physical, with the body, as early as possible after exposure to stressors.

Mindfulness is a quality of consciousness that is associated with control of attention and awareness. When we engage in a movement mindfully, for example eating a chocolate slowly, we have an increased awareness of the movement of the jaws, of the sensations on the tongue, and perhaps of the surroundings in which we can afford to taste the sweetness, thus experiencing positive psychological and behavioral responses.

I learned first-handed that when I play hard in sports in the middle of roaring spectators or when I meditate in a silent temple, I forget everything else. Instead I focus on just doing the sport or the sitting when my awareness fills me in full.

The mind in full mode then calms, restoring inner peace and a sense of oneness. As the body takes the lead, tensions lessen, reversing the negative curve of the mind-play into quietness. This happens more often when I engage with a specific part of the body in an intended action following certain rules, for example in playing soccer or practicing yoga or tai chi or taekwondo or qigong or playing guitar. There is a sense of intrinsic self-control over my being. More so when the activity is self-initiated.

Additionally, experiencing and mastering one movement after another provides a sense of directionality that can reduce the feeling of disorientation or hopelessness. This movement-based mindfulness practice, therefore, may elevate the perspectives of the situation, helping one restore inner balance and reconnect the broken chain between the mind and body. That idea is what planted the seed for my research.

My Story

About thirty years ago, during my work as a undercover special agent, I developed a form of invigorating exercise to cope with the extreme stress I’d experienced doing my job. In Korean this exercise was named Myung-Sang-Juk Momnori (translated mindful body play), based on the meditation and martial art training experience I had since childhood and the knowledge of meridian energy channels that I learned from Buddhist monks.

The Momnori movement was quite helpful in reducing my pre-mission anxiety and rebounding from various injuries and setbacks I had in the work.

Fast-forward 25 years, to Albuquerque, New Mexico. I used this mindful body play, also known as mindfulness-based stretching and deep breathing exercise (MBX), as the core protocol for clinical research conducted as a part of my doctoral thesis, to test whether participation in MBX practice would reverse post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms among those who work in highly stressed environments such as combat soldiers, law enforcement agents, or ICU nurses.

During my preliminary research I found striking similarities between the nature of the work at the frontline as a special agent and the nurses in the Intensive Care Unit facing life and death issues on a daily-basis.

The Study Aims

PTSD is characterized as the long-term presence of the intrusive, avoidant and hyperarousal symptoms, causing substantial social and interpersonal problems and impaired quality of life.

Considering the fact that in any given year, nearly 8 million Americans over the age of 18 are diagnosed with PTSD, current treatments focus on reducing symptoms, improving functional capacity and enhancing quality of life through the use of both medication and psychotherapy, and the treatment efficacy is unclear and residual symptoms are problematic, we need alternative strategies that are accessible at low- or no-cost yet highly effective.

Studies have shown that there is an inverse relationships between PTSD symptom severity and cortisol (the stress hormone) levels; that mindfulness-based exercise, such as tai chi or yoga, has positive effects on PTSD symptoms; that cortisol level increases are associated with symptom improvement, with some evidence showing that cortisol treatment may be an effective method of reducing PTSD symptoms; and that exercise is associated with a transient increase in plasma cortisol in healthy individuals.

So my research team (headed by Mark R. Burge, MD, professor of endocrinology and metabolism at the UNM; Suzanne Schneider, PhD, a former exercise physiologist at the NASA) wanted to explore the relationship between changes in plasma cortisol and PTSD symptom reduction, and examine if MBX practice would normalize cortisol levels and reverse PTSD symptom severity. We set out to evaluate the relationship between MBX-induced changes in cortisol levels and changes in PTSD symptoms as they occur during an 8-week MBX in conjunction with treatment-as-usual, compared to a control group receiving only treatment-as-usual without the exercise component.

The Study Hypothesis

We hypothesized that at the completion of participation in the 8-week MBX program, exercise-induced symptom reduction will be associated with normalized cortisol levels.

Mindfulness enhances a quality of consciousness through control of attention and awareness. Deep rhythmic breathing, focusing on conscious regulation of inhalation, retention, and exhalation, helps to bring the mind to the present moment and connect the awareness of the inner sensations with the outer surroundings, thus often inducing a sense of oneness.

The Mind-body Intervention

The intervention consisted of stretching and balancing movements combined with breathing and a focus on mindfulness. Mindfulness, for our study, was defined as a quality of consciousness that is associated with control of attention and awareness, promoting a direct awareness of bodily movement, sensations, and surroundings, thus often inducing positive psychological and behavioral responses.

The study participants attended a series of 16 standardized, semi-weekly 60-minute MBX. During the sessions, the participants were instructed to attend to the flow of each movement at the present moment, focusing on conscious regulation of inhalation, retention, and exhalation of the breath. Over the course of 8 weeks, the intensity of the exercise increased, but the sequence of the movements was the same.

Significance of The Study

We currently lack a clear understanding of the effects of PTSD on the physiological and neurobiological dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system. Studies evaluating the effect of yoga, tai chi, and qigong exercises have demonstrated PTSD symptom reduction, including significant reductions in reported sleep disturbances, flashbacks and anger outbursts. In healthy individuals, exercise induces a transient increase in cortisol.

It is not yet clear if there is a link between exercise-induced PTSD symptom reduction and a change in cortisol level. The contribution of our study is a better understanding of the relationship between symptom reduction and changes in cortisol level as a result of an exercise intervention.

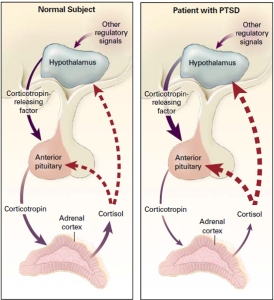

Response to Stress in a Normal Subject (Panel Left) and a Patient with PTSD (Panel Right). Yehuda (2002).

This contribution is significant because it advances our knowledge about the physiological and neurobiologcal regulation anomalies of the autonomic nervous system associated with PTSD and helps us better understand how exercise improves PTSD symptomology. For example, it is currently unclear whether low cortisol level is a risk factor for PTSD or is low as a result of traumatic events.

Making a connection between changes in cortisol levels and PTSD symptoms that result from an exercise intervention advances our understanding of these complex dichotomies. Establishing this link also increases the recognition of exercise as an adjunct PTSD treatment strategy, and improves patient motivation to try exercise as an adjunct to other PTSD treatments.

In addition, the research shows that exercise has the potential to positively address common comorbidities of PTSD such as depression, cardiopulmonary diseases, and metabolic syndrome. As a complementary therapy, exercise may improve current evidence-based psychotherapies and contribute to more effective treatment of PTSD and greater improvement in quality of life at minimal additional expense.

Innovation

Current research has succeeded in identifying treatments that lead to PTSD symptom reduction and also in quantifying the neurobiological markers associated with the severity of the symptoms.

For example, lasting neurobiological changes in combat veterans with PTSD correlate with the manifestation of specific symptoms including: increased 24-hour urinary norepinephrine positively correlated with intrusive traumatic memories; and low 24-hour urinary cortisol levels correlated with a failure of normal memory consolidation.

Despite the advances made in the areas of pharmacology, psychotherapy, and biology as they relate to PTSD, we still lack a complete understanding of the dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system in PTSD, and residual symptoms remain problematic.

The goal of our study was to uncover the relationship between cortisol and exercise-induced PTSD symptom reduction. Because this approach is rooted neither in psychotherapy nor in pharmacology, it represents a significant departure from the status quo and has the potential to lead to the development of an effective new complementary therapy for this common and devastating disorder.

Meditation practice strengthens connections between brain cells in the insular, a hub for autonomic, affective and cognitive integration, and improves emotional control and self-regulation.

Literature Reviews

Studies have shown that mindfulness-based exercise interventions lead to symptom reduction in patients with PTSD. For example, Vietnam veterans who practiced yoga for six weeks showed a significant reduction in depression, sleep disturbances, flashbacks and anger outbursts.

What is less clear is the impact of exercise on the neurobiological anomalies associated with PTSD such as reduced cortisol level and increased catecholamine levels.

It has been established that individuals with chronic PTSD suffer from low cortisol levels; that low cortisol levels are correlated with PTSD symptom severity; and that cortisol levels may change in relation with symptom modification.

In healthy people, we know that immediately following exercise, cortisol levels are elevated; and that after exercise at a lower work rate (55 % VO2max) for a longer duration, plasma cortisol concentrations rise higher than those observed at a higher work rate (80 % VO2max).

The question that I had was whether the resting Ante Meridiem (AM) plasma cortisol levels increase in individuals with PTSD as a result of exercise, and how an exercise-induced increase in cortisol relates to PTSD symptom reduction.

There is considerable research to support the neuroprotective benefits of exercise for people with chronic stress. Moderate-intensity exercise has been shown to have neurobiological effects on chronic stress-related symptoms including improved regulation of the serotonergic system, counteraction of degradation of the hippocampus caused by chronic stress, reduction of neurobiological sensitivity to stress, and normalization of catecholamine levels.

There is sufficient data to suggest the positive relationship between exercise and PTSD symptom reduction. More well-established is the link between cortisol levels and PTSD symptom severity. For example, among veterans who served in Vietnam, individuals with a current diagnosis of PTSD had significantly lower adjusted plasma cortisol levels than individuals who did not have a diagnosis of PTSD.

To read more, please visit here.